165 Officer Cadet Training Unit, Dunbar.

PLEASE NOTE - A CONTACT POINT FOR THOSE WISHING TO APPEAL FOR INFORMATION ABOUT A RELATIVE WHO TRAINED AT 165 OCTU, DUNBAR, CAN BE FOUND AT THE END OF THIS PAGE.

Dunbar High Street looking south east [DH].

165 Officer Cadet Training Unit (O.C.T.U.) was to operate throughout the war, records showing that it was still providing training courses in April 1944 and may well have gone on later than that. Soldiers came from a wide range of regiments rather than from one or two. The Royal Scots Greys and later the Sherwood Foresters, were stationed for a time in Dunbar soon after Dunkirk but were not part of the O.C.T.U..

At the O.C.T.U. officer cadets, easily recognisable from the white bands around their forage caps, underwent long or short courses in all aspects of their future work under the guidance of a number of permanent Regular Army instructors. The courses lasted from four to six months and probably shortened as the war went on. A firing range was handily placed on the beach area close to the present day East Links Family Park. This range was well used by all units based in East Lothian in addition to the cadets of the O.C.T.U..

The cadets were fed in two canteens, one where the Supersave shop is now and the other accessed by the close beside the Lothian Hotel. Mrs Low ran the latter. They also ate in their ‘hotels’.

Cine Film Of 165 O.C.T.U. In 1940

It is possible to see a great deal of what the Cadets got up to in their periods of training at Dunbar in 1940 as an amateur 16mm cine film was made by Cadet Harry Birrell during his training. The atmosphere the film projects is still a happy one as the film was shot prior to the fall of France, Dunkirk and the darker days of the Battle of Britain. It is difficult to imagine such a film being sanctioned at any other time in the war. Among other aspects of life, the film shows the Cadets marching around the town, out on bicycles on exercise and amusing themselves in Dunbar's open swimming pool. You can access the film via the National Library of Scotland, Ref. No. 2672.

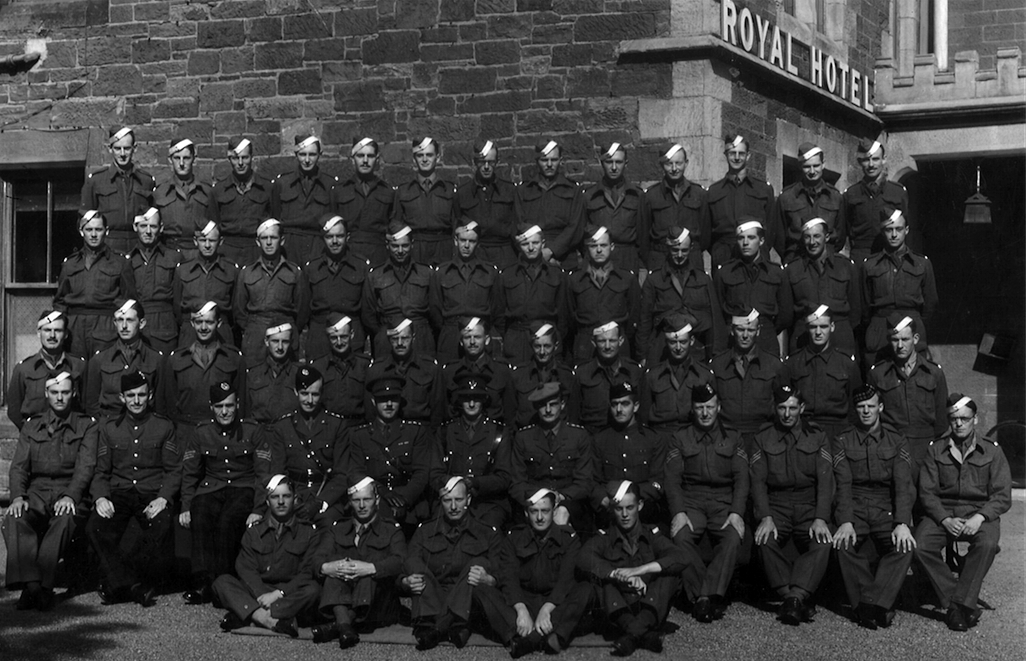

Group of trainee officers in C Company probably at the end of their course at Dunbar in September 1942. The poet Sidney Keyes, is top row, second from the right. Rod Madocks’ father, JE Madocks is third row down, third from the left and Trevor Howard is on the same row ninth from the left. [Source: Rod Madocks].

Famous Names At 165 O.C.T.U., Dunbar

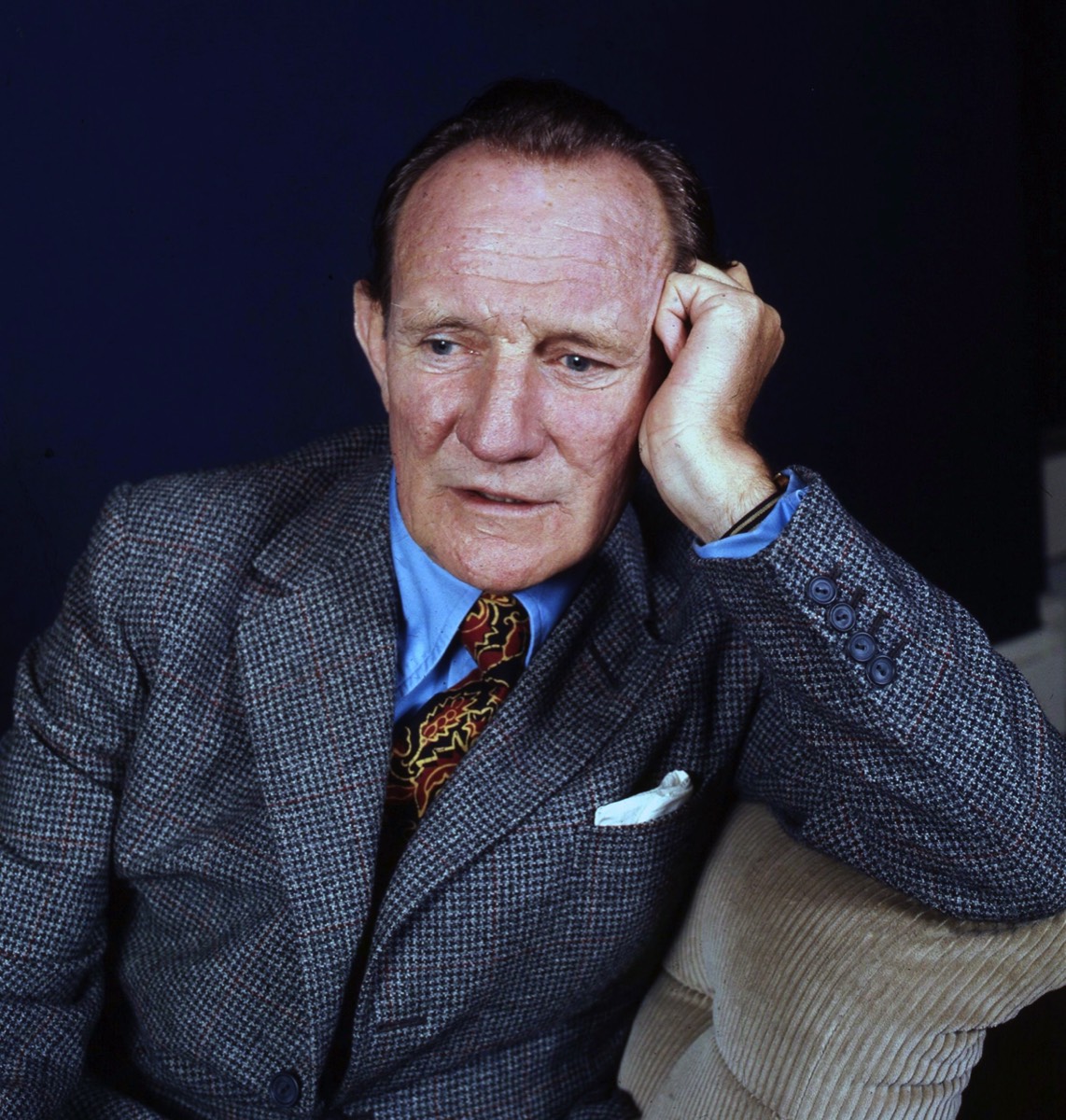

In addition to those who were to make their names in the crucible of the war, were others who made it in the performing arts. After an unsteady start, first attempting to join the R.A.F. and then failing to make a mark in either the Royal Corps of Signals or in coastal artillery, the actor Trevor Howard was posted to Dunbar for training. There he found that the adjutant was a bit of an amateur thespian who was more than willing to persuade Howard to put on a play in which both were to act. Training, however, wasn’t much to Howard’s taste and he found his time at Dunbar somewhat on the boring side of tedious. Later service was no more to Howard’s liking and he was eventually invalided out of the army.

A less appealing side of the actor has been revealed by Rod Madocks in his recent book, “The rising flame: remembering Sidney.” [Shoestring Press] In this Rod wrote about another famous Dunbar trainee who was in the same draft as Howard, the poet Sidney Keyes. Keyes had studied at Oxford and had written two books while there: “The Cruel Solstice” and “The Iron laurel”. He later wrote a number of poems, a number of which were written while serving in 165 OCTU. In his book Rod wrote about how ‘...Howard bullied Keyes on the course. Howard would be thrown out of the army in 1943 and would make up stories during his filming career that he had won the MC and served in the Airborne Forces.’ This information came from Rod’s father who was also in the draft which included Howard and Keyes in September 1942 at Dunbar.

Trevor Howard.

A popular band leader of the day, Lou Praeger, also trained at Dunbar. He was the leader of the Romano Restaurant Dance Orchestra.

Captain Norman Leask

(on the right)

Memories Of 165 Officer Cadet Training Unit, Dunbar

2nd Lieutenant Norman Leask (later Captain), 1st Battalion the Cameronian Rifles, remembers training at 165 O.C.T.U. in 1940. I make no apology for including the following lengthy description of training life at Dunbar: few things are better than the voice of one who was there:

Invasion Scares

"‘A’ Company was formed in early June 1940 around the time Italy had joined the war and the evacuation of France was not fully completed and the soldiers were ordered to report to the Roxburgh [hotel] by 5.00pm about the 15th. Along with another ninety odd personnel I arrived on time.We were met by our Company Commander and were told the ‘Balloon’ had gone up and the Dunbar O.C.T.U. would be formed into a Battalion and rushed to the south of England to repel invaders. 1730 Company paraded to be informed the Germans were planning to invade Southern England and a pincer movement from Norway was expected to invade East Lothian at any moment.

We were each issued with a ‘two star’ rifle: ‘one star’ meant it was not serviceable and ‘two star’ meant it was dangerous to fire! We also got five rounds of .303 ammo per man, one packet of 3d (1.5p) McVitie and Price tea biscuits, one Mars bar and one water bottle. This was our rations for forty-eight hours!

Sleep was a commodity we did not have much of. We had to patrol three miles of coast from the Barns Ness lighthouse from dark till one hour after dawn – we were supposed to be looking for anyone landing. We had three half hour spells as sentries which meant two hours on, two hours off and a second spell of one and a half hours. We used to toss as to who was on first and then we did three and a half hours continuously instead of breaking our sleep which, if you were last on, would have meant your being awake from 3.30 a.m. with a full day’s training till 10.00 p.m. Not so funny!

We were due to attend a Sunday service of Thanksgiving on Sunday 15th September 1940, but on the Saturday evening we were alerted to ‘Stand To’ about 10.00pm. The British Legion dance was stopped, and all the pubs scoured for cadets in various degrees of inebriation. We spent the whole of that Sunday until late in the night manning our positions on the beach. The people of Dunbar were kindness itself, but I often wonder if they really knew that it was a collection of boys aged nineteen or in their early twenties with five bullets each who had protected them as they slept safely in bed that night!

Training [Training Often Lasted Six Months]

Our routine was reveille at six a.m., work till one. Afternoon off? And lectures five to eight p.m. Lights out came at 10.15 p.m. except on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays when we had to be back in quarters by 23.59 hours. ‘Afternoon off’ consisted in being taken to Belhaven Beach to dig trenches whilst civilians were erecting tank obstacles and pill boxes. We also dug air raid shelters across the road from the Albert Hotel.

Most of the training was on the beaches, at Spott Dod, Spott, the reservoir and over the hills. On returning from exercises marching along we sang all the bawdy soldier’s songs like ‘I’ve got sixpence, pretty little sixpence’ and others like ‘They say there’s a troopship leaving Bombay’, and one about a dance in Kirriemuir. Entering Dunbar, we had to ‘March to attention’, meaning we were not allowed to sing or whistle at any of the pretty girls we saw. We did get a warning that if any Cadet was seen out with one young lady, who was nicknamed the R.T.U. Blonde, he was immediately [to be] returned to unit.

The parade ground stretched away from the back of the barracks and is now a park and the site of the swimming pool.

[D. H.]

The Barracks

We only used the Square for endless hours of drill. The Drill Sergeant Major (Cameron Highlanders) was a soldier from the 14-18 war. Due to a slight aspiration and slur he could only pronounce Stand Still as Sschtand Sschtill. When the drill squad were under-performing he would shout a the top of his voice: ‘You are schwinging your arms like a lot of Schee Gulls’. When one laughed you were sent round the square at the double.

Air Raids And German Parachutists

The first air raid warning about the end of June was on a beautiful moonlight night and we rushed to our trench and civilian women and children asked if they could join us since no shelters were available for civilians. We invited them in. About twenty minutes after the alarm we saw a German bomber being followed and shot down into the sea off Dunbar.

As a precaution against paratroops landing when out on manoeuvres we always had a Platoon (thirty men) on bicycles to follow our three X fifteen hundredweight trucks. Three were needed to move 100 men. Our sector, in case of a landing, was about half a mile south of the lighthouse where we had dug trenches near the beach. On a night training scheme away up in the hills, Verey Light signals were fired telling us to make for the beach. Since it was a moonlit night the trucks arrived OK but the bicycle platoon came racing down the hill and into a dark wood on a corner and all ended up in a heap – our first minor casualties.

Relations With The Locals

For the four months O.C.T.U. training Dunbar was a pleasant place to be. I would say that the relationship with the public and the Cadets was good. As we were training to be officers and Gentlemen there was a code of conduct (roughly obeyed!).

As a normal practice an officer always salutes a lady and, for practice, any lady we met was saluted. This had amusing consequences of a summer’s evening when the good people of Dunbar went out for a stroll. [Sometimes we would meet] one of our Church of Scotland canteen ladies. All of the Cadets who knew her would chuck her [a salute] in passing. Poor hubby had to lift his bowler or trilby to acknowledge the salutes and with twenty or thirty Cadets walking along the main street he could easily have appeared in a comedy sketch with John Cleese, et al!

In our spare time (?) one Saturday we were asked to volunteer to help a farmer get his hay gathered at a farm near the coast towards North Berwick and this we did in record time. We were given a huge buffet meal and bounteous drinks as a thank-you and we sang all the way back to Dunbar that evening.

On our digging activities we dug a very long trench for civilians on the green above the swimming pool and were still digging about 11pm when a lady from a house opposite asked how many were working and we replied about ten or twelve. Shortly afterwards she came over with tea and cake served in china cups of different patterns. I am sure her ‘Wedding China’ was used. It was a very kind act and much appreciated. Unfortunately we weren’t allowed to send a ‘thank-you’ note: security!

Relaxation

On Friday and Saturday evenings we were allowed out to play. We often headed to the Church of Scotland canteen which was near the main street and down towards the sea. The George Hotel was a frequent howf if we had money. Often on a Saturday night the elderly lady in the hotel would be pouring out pints, etc., and on Sunday morning she would be handing out Hymn books as we attended Church Parade. Farewell parties were usually held in the George when we would have a ‘snooker’ or a ‘booze-up’ with our officer instructors.

Our army pay was fourteen shillings per week (70p) which luckily was augmented by our parents. When we were flush we had a slap-up meal at an Italian restaurant in the main street at the corner on the left. The owner was in fear of having his window put-in and as a precaution had a photograph of himself in British Army uniform with his 1914-18 war medals in a case in the window. He used to like having the troops in as customers and we had real eggs, not powdered, if we went in when his café was quiet.

The Castle Bar, Dunbar [DH]

The Castle Bar In Dunbar

Our favourite pub when in D company was the Castle Bar next to the Barracks. In the upstairs room we had a piano and if we couldn’t sing, we were just noisy! The permanent staff from the Barracks were in the bar downstairs so we knew most of them. At night guards were mounted outside the main hotels, more in the Army tradition of ceremonial guards rather than being capable of defending our shores. The sentries marched up and down as if on a parade ground.

Vandalism was still alive in those days – hanging at the foot of the stairs in the George was an old moth-eaten stag’s head (dirty and untidy). At one of these parties two Cadets took the poor beast off the wall, took it to the bathroom and gave it a shave and a wash and brush up. The poor residents who had left their razors in the residents’ bathroom were not amused! Luckily no disciplinary action was taken, and the George had the only bare-faced deer in the county!

Deys, the photographer on the Main street, did a roaring trade with the Cadets wanting photographs to send home to wives and sweethearts. The swimming pool was in use throughout the summer. In the morning we used it especially after a mile or two run. We were taken to the pool and everyone had to dive or jump off whether they could swim or not. Sometimes in the afternoon we would sunbathe and catch up on our sleep if we had been on night patrol or guard duty.

The two records which were ‘Top of the Pops’ in 1940 were ‘We’ll meet again’ (Vera Lynn) and ‘The Woodpecker’s Song’ (The Andrews Sisters). I’m sure one could hear the latter as far away as East Linton.

The Golf Course was still open for play with one or two man-made hazards. One was an old milk lorry which was our target for practicing throwing Molotov Cocktails.

Some Interesting Moments

Musselburgh had a racecourse meet on a Saturday afternoon in September. As we were not allowed to leave Dunbar we could not attend. However, a few Cadets went down to the station at Dunbar, looked to see if there were any officers about and removed their white bands and epaulets and travelled as ordinary soldiers. Needless to say, this absence was not discovered, or they would have been court-martialled.

On one occasion – a Saturday night – a Lance Corporal (on the permanent staff) walking past the Bayswell Hotel told the sentry his companion was a ‘spy’ and had been asking him the strength of troops in the area, etc. The civilian ran off down the Bellevue Road with the troops in pursuit and he was winning until one of the cadets threw away his rifle and helmet and ran after him and tackled him. He was arrested and handed over into custody. We subsequently heard that the civilian spy was butler to one of the titled gentry in the Borders."

[Source –personal account compiled and edited by site author from two accounts written by Norman Leask in September 1999]

Reminiscences of Captain Rhoderick Macleod, 2nd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders.

These memories were also of training at Dunbar in 1940 and paint a very similar picture to that painted by Norman Leask.

“After basic training the Etonian, several others from another squad and myself, were selected to go for officer training at 165 OCTU at Dunbar on the East Coast. Being the tallest of the draft and a lance corporal by that time, I was the right-hand marker for the squad. Andy Drummond, the Regimental Sergeant Major, emerged from his office and inspected us. His first words of encouragement to us were unforgettable – “I knew that things in France were not going that well but Jesus they cannot be this bad”. The time was just before Dunkirk.

165 Officer Cadet Training Unit at Dunbar, in common with similar establishments elsewhere, had the unenviable task of turning out officers for the rapidly expanding Army. The process was scheduled to take six months and was very hard work indeed. The assumption was that, although we all came from various infantry regiments and had been ‘trained’, we actually knew nothing and therefore had to start all over again with the simplest of drill movements. The barrack square was in the centre of Dunbar town and the local inhabitants enjoyed… watching us being chased around.

As Officer Cadets the instructors addressed us as “Sir”. One unfortunate ex-cavalryman once had the temerity to address our Company Sergeant Major as “Sgt-Major”. The bawled reply was that “Mr. Whilloughby Sir, I’m Sir to you Sir and you are Sir to me Sir, and don’t you ever forget that.”

Our time at Dunbar coincided with the fall of France. As a result, we had to study and drill during daylight hours and then march off to the East Lothian beaches, man the coastal defences and act as first-line anti-invasion troops overnight. In the morning we were then expected to march back and appear neat and tidy for another day’s instruction. Our night-time post was defending Belhaven beach, a stretch of sand several miles long. Had the enemy chosen to come we could have done little about it, for we had only 25 rounds each.

I have never been as fit at any time in my life before or since. The final exercise involved marching over 70 miles and fighting a rearguard against an ‘enemy’ who covered the same distance in SMT buses. What nearly killed us, however, was the brass band of the Sherwood Foresters who thought they would do us a favour and help us by playing us back into camp over the last stretch of five miles.”

[Source - www.scotsatwar.co.uk]

Harry Fell relates some of his memories of his days in training at Dunbar.

“I enjoyed my four months officer cadet training at 165 O.C.T.U. Dunbar having come up from Brighton in the Royal Fusiliers and having been posted into ‘C’ company billeted in the Albert Hotel. All the hotels had been taken over by the military. After a few weeks of initial training drill, weaponry, administration, etc., ‘C’ company was then transferred to the Bayswell Hotel.

Training and discipline were strict, but not unduly so, and our free time was spent at the open-air bathing pool, which is now demolished. One Sunday afternoon, the pool being busy with bathers and spectators, a German Heinkel III closely followed by a Spitfire, flew at eye level across the front of the pool. Both pilots could be clearly seen, and I understand that the Heinkel was brought down at Co’path.

Besides all the intense training many humorous incidents occurred during my service in Dunbar. I well remember standing in ranks on the High Street outside Jimmy Laws hairdressing shop being inspected by Sgt. Maj. Grant. He would come up behind you and if your hair was too long, he would give it a good pull and repeat his well-known saying: ‘Another candidate for Harry Roy’s band. Get it off!’ I remember once he threatened to march us towards the sea and forget to give us the about turn.

Prince Bernard of the Netherlands.

To my knowledge live ammunition was not used at 165 O.C.T.U., though Thunder Flashes certainly were and regularly so.

Dunbar in those days was certainly a busy place and the New Inn Barracks, now an Old People’s Home, was used as the Quarter Master’s Store.”

[Source: Letter written by Harry Fell, 15th September 1999]

Mrs Fasson: A Nurse Remembers

In 2003 Mrs M.F. Fasson wrote about her experiences as a nurse in Dunbar. She wrote: “I was called up for the army early on in the war and I nursed in the little infirmary hospital within Dunbar Barracks. The 165 Officer Cadet Training Unit took over Dunbar. Oddly enough I discovered quite a few I knew when they came into hospital for the usual jags (ATT, TAB, etc.) or bad backs. It became a small world sometimes: anything serious was sent to the Castle in Edinburgh or Peebles.”

[Source: Letter dated 15th October 2003]

Note: In Personal Reminiscences, George Gillan has one or two things to say about the OCTU cadets.

"I am currently researching my Father's military service during WW2. His details are as follows.

During 1938 and 1939 he was a student at Aberdeen University and was a member of the university's Officer Training Corps. On the 22 September 1939, following the outbreak of war, he enlisted with the Gordon Highlanders Territorial Army. His service number with them was 2882759. On the 10 October 1939 he was posted to the 165th OCTU at Dunbar.

On the 8 March 1940 he was discharged from 165 OCTU, having received a commission and posted to the York and Lancaster Regiment on 19 March 1940. He remained a York and Lancaster Officer for the duration of the war, although from March 1942 he was posted with the Devonshire Regiment for the rest of the war."

John is especially keen to know why his father was posted to an English regiment instead of a Scottish regiment.